Baobab

- DIVISION: Tracheophyta

- CLASS: Magnoliopsida

- ORDER: Malvales

- FAMILY: Malvaceae

- GENUS: Adansonia

- SPECIES: (nine)

OVERVIEW

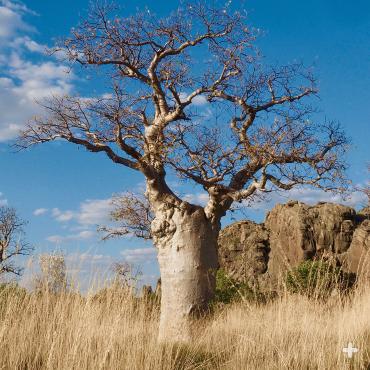

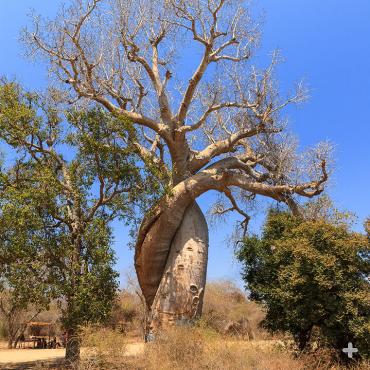

Icons of the African savanna, the dry forests of Madagascar, and Australia’s Kimberley region, baobabs are trees like no other. A thick, bottle-like trunk rises to support spindly branches. Baobabs are deciduous, and during the dry season (which can last up to nine months), the bare branches of a baobab resemble a gnarled root system, and make these trees look as if they were pulled up by the roots and pushed back in upside down.

The baobab is not just one tree, but nine species in the genus Adansonia. Two are native to mainland Africa, six to Madagascar, and one to Australia. All nine inhabit low-lying, arid regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, you find baobabs rising above hot, dry scrublands and savannas. In Madagascar, baobabs are important members of the dry deciduous forests in the western part of the island. In Australia—where they are known as boabs—they stand sentry in open savanna woodlands. What do all these regions have in common? A short wet season and long, hot, dry season. Most trees would shudder (if they could) at these conditions, but baobabs thrive.

Nicknamed the “tree of life,” baobabs play a key role in their ecosystem. They help keep soil conditions humid, promote nutrient recycling, and prevent soil erosion. And, they are an important source of food, water, and shelter for various birds, reptiles, and insects. In fact, a mature baobab tree creates its own ecosystem. In Africa, monkeys and warthogs devour baobab fruit and seedpods, and weaver birds stitch their nests into a baobab’s huge branches. Galagos—also known as bushbabies—and fruit bats lap up baobab nectar. Elephants and other wildlife sometimes eat spongy baobab bark, which provides moisture when water is scarce.

CHARACTERISTICS

Baobabs can be enormous. While the smallest species, the Madagascar’s fony baobab A. rubrostipa grows to 16 feet (5 meters), the largest, Africa’s A. digitata grows to about 82 feet (25 meters). The largest baobabs may have a girth (circumference) of 82 feet (25 meters) or more. Bark is typically smooth and shiny, ranging in color from pinkish-gray to copper. Baobabs can regenerate bark that’s stripped by elephants, other browsing herbivores, or people.

The bulbous trunk of a baobab—a site of water storage—is usually more or less cylindrical. In some varieties it is more irregular, with folds that channel rain and dew. Creases and hollows provide homes for small reptiles, insects, and bats. Rather short, stout branches are gnarled and twiggy at the tips—and bare of leaves much of the year. These trees are drought-deciduous: they drop their leaves during the dry season, an adaptation for conserving water. Leaf shape ranges from simple ovate leaves to palmate leaves with five to seven finger-like leaflets (in A. digitata).

Each large flower—a mass of stamens surrounded by petals that range from white to orange (depending on species)—hangs from a long stalk. The fragrant flowers open at night. Each one lasts for only about a day, but while in bloom, its plentiful supply of nectar attracts nocturnal pollinators, such as fruit bats, and moths and other insects. Only a few flowers are open at a time, encouraging pollinators to move from tree to tree and promoting cross fertilization.

Fruits are large, egg-shaped capsules that (in some species) can be nearly 8 inches (20 centimeters) long. Eventually, the outer shell becomes hard and woody, and covered with fuzzy brownish hairs. Unless a monkey or a person comes along to eat it, a seedpod hangs on a tree intact until it blows off in the wind. The fruit dries into a powdery pulp that covers the bean-like seeds inside.

USES

Across Africa, many people eat most parts of the baobab—including roots and small sprouts. People boil and eat the leaves, and even flowers are edible. Mixed with water, the powdery fruit pulp makes a refreshing drink. People snack on roasted seeds or use them to brew a coffee-like drink. Foliage sometimes serves as fodder for livestock. With the tree’s fibrous bark, mats, ropes, baskets, paper, cloth, nets, and fishing lines are made. Its wood is used for fuel and timber, and traditional remedies make use of various parts of the baobab.

CONSERVATION

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) evaluates the conservation status of plant and animal species, with the particular goal of identifying those at risk of extinction. The results are published in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The IUCN has assessed six of the nine baobabs. It lists three of the Madagascar species as Endangered and the other three Madagascar species as Near Threatened. The two African varieties and the Australian boab have not been assessed.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an agreement that guides international trade in specimens of wildlife. CITES creates lists, or appendices, for plants and animals for which trade controls are necessary. CITES lists one Madagascar baobab, A. grandidieri, on Appendix 2—species that are not currently threatened with extinction, but that may become so without trade controls.

Experts have noted a rapid increase in baobab deaths in southern Africa. Of the continent’s 13 largest baobabs, 9 have collapsed and died. The cause is unclear, but scientists suspect that global climate change may be playing a role in the demise of these trees. In South Africa, the baobab was declared a protected tree under the Forest Act in 1941.

BAOBABS OF THE WORLD

Madagascar

- A. grandidieri

- A. madagascariensis

- A. perrieri

- A. rubrostipa

- A. suarezensis

- A. za

Africa

- A. digitata

- A. kilima

Australia

- A. gibbosa

HOLLOW

Some old baobabs tend to develop a hollow center. In some places, people have used hollow, supersized A. digitata trees for storage, shelter, prisons, and post offices.

TREE PUB

The “Sunland Baobab”—an enormous tree in South Africa—became a tourist destination when landowners built a pub inside its hollow center. It was said to be 72 feet (22 meters) tall and 155 feet (47 meters) in girth. The Sunland Baobab died in 2017.

AKA

Baobab trees are known by many common names, including lemonade tree and cream of tartar tree. In various parts of Africa, they are known as kremetartboom (Afrikaans); isimuku, umShimulu, or isiMuhu (Zulu); mowana (Tswana); and muvhuyu (Venda). Aboriginal Australians have different names for the tree, too, including largid (Bardi), gerdewoon (Miriwoong), and jungari (Woolah).

SHOWING THEIR AGE

Baobab tree trunks don’t show clear growth rings the way many trees do, so scientists tested a radiocarbon dating method to determine the ages of some large baobabs. The results suggest that some of the largest, oldest baobabs may be more than 2,000 years old.

BIGGEST, OLDEST

African baobabs A. digitata are some of the biggest and longest-lived flowering plants alive today.

BUZZ

African honey bees Apis mellifera make hives in baobabs.

ONE OR MANY

Recent research suggests that baobab trunks are made of multiple stems that fuse together, around an empty space. According to other botanists, it’s the baobab’s ability to regenerate stripped bark that explains its unusual growth pattern.

WATER STORAGE

Baobabs store water in their thick, fleshy trunk, making them the largest succulent plants in the world.